02.10.2023 | Johannesburg, South Africa

Someone recently asked me what the most grueling air ambulance retrieval is that I have ever done. Seeing that we work in Africa with so many challenges on a daily basis, this is a difficult question to answer. There have been many grueling retrieval missions throughout my time at Air Rescue Africa, but what immediately came to mind was Covid-19. Not a particular case but a combination of factors that often made most of these retrievals extremely taxing. At the risk of nobody wanting to read anything to do with the pandemic, I still think it is the right time to reflect, pen down our response to the pandemic in Africa and share it with a wider community.

First, a bit of background

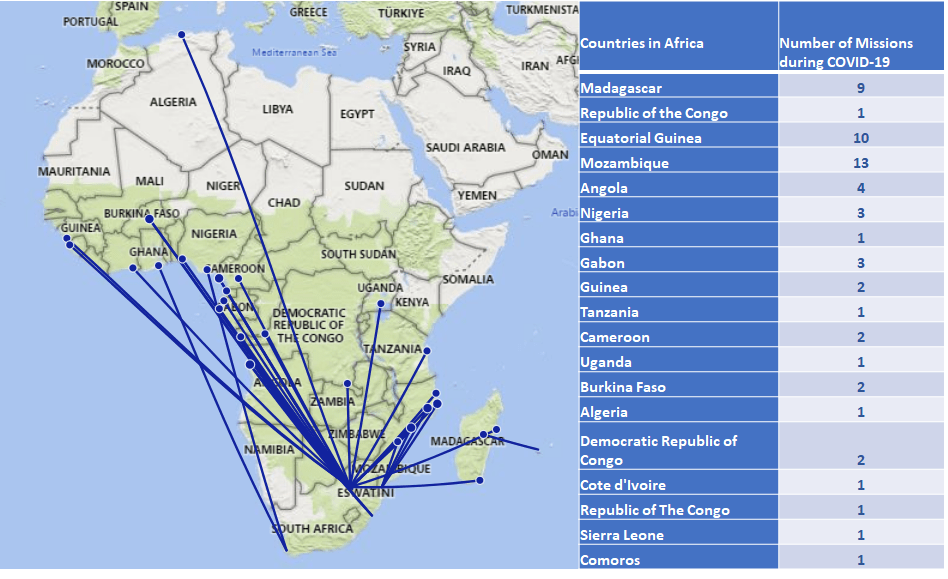

During the course of the pandemic, just in Africa we did 59 air ambulance retrievals for patients with Covid-19, while continuing with non-Covid case activity. All of these were international retrievals from 19 different African countries. All missions were performed on Hawker 800 and Hawker 800xp aircraft. For the largest part of the pandemic all non-ventilated patients were transported in a Portable Medical Isolation Unit (PMIU), the Isoark N36-6, but more on that below. 15 patients (26%) were transported intubated and ventilated (not in the PMIU). Our average total flight time was around 10 hours. The longest patient contact time (from arrival at the bedside to handover at the receiving facility) for a ventilated patient was 15 hours and 15 minutes (Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso – Durban SA).

As most other healthcare institutions at the time, we faced all the challenges the pandemic would throw at us, but the way our medical crew and operational personnel responded to them was nothing short of remarkable (and this can also be said about the medical society in general). The mammoth task that lay ahead of us would eventually prove to be a test of character and resilience for every individual involved.

The challenges

There were many challenges, and trying to mention them all would be impossible, but some of the ones that stood out were:

- Uncertainty: Early on there was an element of uncertainty in everything we did. There was obviously very limited information available about the disease and medical professionals all over the world were dealing with the uncertainty of how to best manage these patients from a medical point of view. But uncertainty about something else weighed even heavier on our medical crew, their own safety. It was impossible to confidently say what the best way was to transport these patients safely. The safety of both the patient and crew was obviously of utmost importance, leading to the most prudent approach: to go about the disease the same as we would do with any other highly infectious disease. Our initial procedure was based on what we used for highly infectious pathogens such as Viral Hemorrhagic Fever, etc. That had many downstream implications, both for the medical crew and the patients.

Apart from the uncertainty about the disease, there was also uncertainty about the operational aspects of doing air ambulance missions. Every country had unique entry requirements, and one never really knew what the officials on the ground would come up with once you have landed. Entering back into your own country (South Africa) also brought along an additional risk of a compulsory isolation period in a dedicated isolation facility, something often feared, but fortunately never materialised. Suffice to say that we had to endure many unfamiliar processes that were continually changing.

- The isolation unit (PMIU). For the sick patients, this was obviously cumbersome, but unfortunately, there were few alternatives at the time. The prospect of being stuck inside a plastic tube for a prolonged period of time often proved to be daunting. But weighed against the risk of remaining in a resource-limited setting and any further deterioration in their condition potentially being fatal, they were willing to take on the PMIU. For us as medical crew the PMIU also became a challenge to say the least. To skip most of the details one can likely appreciate that it takes a lot out of you to set the unit up (with iv-line-, O2 tubing-, monitoring cables ports prepared beforehand), get someone into the unit, get the unit loaded into the aircraft and try and manage the patient’s condition in the best possible way while inside. And once you have handed over your patient at the eventual destination, decontaminating it to get it ready for the next one. All this being done in full Hazmat suits, with N95 masks, goggles, etc. in scorching temperatures and oftentimes extreme humidity, typically encountered in Africa – which brings me to the next challenge…

- The heat and Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). The conditions in which these missions were performed for the most part were extraordinary. The heat and humidity that we experienced in full PPE were extremely demanding and I experienced firsthand what an impact this had on performance, decision-making, and teamwork. Often you were soaked in sweat to the point where your shoes felt like you were walking in the pouring rain. Apart from the obvious risk of dehydration, hyperthermia, and hypoglycemia, this brought about, the PPE that you had to wear often further complicated matters. Face masks had a definite impact on communication and goggles fogging up made performing procedures under these circumstances even harder.

- Complex patients and critical decision-making. Stabilising sick patients in an unfamiliar environment wearing full PPE in the heat and humidity is something we quickly become accustomed to. All human factors relating to these types of cases were ramped up to a different level. For example, intubating a hypoxic patient in ideal circumstances is already challenging, combining this with all the other things mentioned above, turned this into a real test of one’s clinical and decision-making skills. To add to the complexity, because of language barriers, we often had to rely only on our team of 2 (doctor and nurse) to perform all necessary procedures. Not being able to get a proper handover or effectively use the extra pairs of hands that the local team has to offer is something we are not unfamiliar with in Africa, but in these challenging times, the effect thereof was felt even more pertinently.

Furthermore, the medical leadership was often faced with difficult decisions regarding the appropriateness of a request for transfer or a patient’s fitness to fly. This led to the development of a triage tool, based on the limited evidence available at the time, to assist with these challenging decisions.

The response

Despite the obvious risk to oneself, either by spending prolonged periods with an infectious patient in an enclosed space or managing a critically ill patient’s airway (that remains one of the highest risk interventions for a healthcare provider to contract the virus), our medical crew were committed to help these patients to the best of their abilities and execute each mission successfully. It was this selfless dedication to patients that made them confront all challenges head-on and endure whatever challenges came their way.

As Winston Churchill famously said: ‘Never let a good crisis go to waste’, our medical crew responded in the most emphatic way to the pandemic. Looking back, I am convinced that this period of time contributed significantly to the development of many of our air ambulance systems and most importantly, our clinicians. In a very short period, we became extremely efficient at executing missions involving highly infectious pathogens, something previously not done very often. Complex airway management and complicated ventilation strategies as well as critical decision-making under pressure were all skills that would not have been developed at the rate it did if it wasn’t for the pandemic.

But perhaps the highlight of the pandemic for me personally was witnessing the resilience with which these clinicians managed every challenge that came their way. Regardless of the circumstances, no one ever refused to go on a mission. No uncertainty was great enough to deter these individuals from making a difference to the patients they were tasked to serve. There were many instances where tears were flowing and it felt like one could not carry on anymore, but somehow, they would find the strength to continue, get through the day, and do it all over again the next day. Despite the heartache and pain of the pandemic affecting all of us, these clinicians could always muster up the courage to take a patient’s hand and comfort him/her in their time of need. I am convinced that never before was a selfless dedication to patients so openly on display as during this pandemic.

To all healthcare workers who took up the challenge and endured to the end, I salute you!

Dr. Ulrich Carshagen

Lead Flight Physician at Air Rescue Group